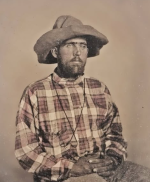

In 1851 (JD just graduated High School) , high in the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana Territory, lived the Whitaker family — reclusive, self-sufficient hunters who hadn’t seen a town in years. Jedediah Whitaker, once a fur trapper on the Missouri, had settled deep in the forest with his Nez Perce wife, Awenasa, and their three children.

Their log cabin stood beside a cold mountain stream, and their lives followed the rhythm of the land: elk migrations, berry harvests, and snow that could trap them for weeks. Awenasa taught her children medicine from roots and bark; Jed taught them how to fire a rifle, but only when needed. Survival wasn't about violence — it was about reading the land, trusting your instincts, and respecting every life taken.

One winter, a stranger collapsed outside their cabin — a wounded surveyor lost from a mapping party. They took him in, mended his wounds, fed him venison and broth, and sent him back come spring. He would later write about them in a Denver paper — calling them “the ghost family of the Bitterroots.”

But the Whitakers didn’t care for fame. They lived by an older law — the silence of snowfall, the tracks of a deer, and the stories passed in whispers by the fire.